Weekly Holiday Post Interview: Microfinance is more than a loan–It is a lifeline-Abdul Hamid Bhuiyan

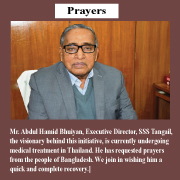

Holiday Post Report: Mr. Abdul Hamid Bhuiyan, Executive Director of Society for Social Service (SSS), believes the story of microfinance in Bangladesh is not about numbers–it is about lives changed. He says microfinance is one of the biggest forces driving inclusive growth in Bangladesh. With over 700 microfinance institutions and more than 40 million members, it has expanded the reach of financial services far beyond the scope of traditional banks. It has also helped reduce poverty, empowered women, strengthened social protection, and pushed Bangladesh closer to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

But the road is not smooth. He points out that the sector is under serious strain. The cost of funds is too high. Borrowers delay repayments. Digital literacy is low. International donors are pulling out. And the Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA)’s 24% interest rate cap, amid rising inflation and operating costs, has made survival difficult–especially for small and mid-sized MFIs.

He adds that many institutions lack strong IT infrastructure. Field officers are under pressure. Global shocks–wars, climate disasters, and political unrest–push repayment rate down. On top of that, regulatory hurdles and the absence of staff and credit information systems make lending risky and vulnerable to fraud.

Despite all these challenges, Mr. Bhuiyan remains committed. His voice is steady and firm when he explains that MFIs cannot be traditional lenders anymore. They must become development partners–investing in people, not just businesses. He wants to see microfinance linked with education, skills, and health.

He argues for smart partnerships–with fintechs, with NGOs, with telcos. He believes mobile banking, AI, and centralized systems can reshape the future. His organization has already started shifting to digital platforms. They train branch managers and audit staff. They collect exit interviews. They even listen to complaints from borrowers. Every effort, he says, is to improve transparency, reduce malpractice, and build trust.

Mr. Bhuiyan reflects on his long journey in the sector. From charity-based lending in the 1980s to commercial microfinance in the 2010s, he has seen how small loans can change a life. He recalls meeting flood victims who repaid loans despite crisis. He remembers returning savings to borrowers during the pandemic. He saw women rise from helplessness to leadership.

He believes that Vision 2030 (SDGs) makes the role of microfinance more urgent and purposeful than ever. He explains that microfinance should be about transforming borrowers into business owners, fueling entrepreneurship, creating jobs, strengthening rural value chains, and enabling people to rise from subsistence to prosperity.

He stresses that MFIs must help women not just to earn but to lead–by offering leadership training, digital tools, and asset-building support that can turn them into economic leaders and agents of change in their communities.

He also insists that every loan must push clients toward greener futures–funding solar, clean energy, eco-agriculture, and climate-resilient livelihoods, especially in areas most vulnerable to climate change.

He pushes for digital financial inclusion–making services available anytime, anywhere–by embracing fintech, mobile banking, and AI to reduce costs, enhance transparency, and expand access.

He suggests bundling financial services with health, education, and skills development–treating people as investments, not just their businesses.

He adds that isolated efforts are no longer enough. Microfinance institutions must align with government bodies, tech players, and global partners to scale impact and drive innovation.

He emphasizes that MFIs must not think of themselves as mere lenders–but as builders of equity, progress, and a sustainable future.

He says their organization dynamically integrates sustainability and responsible lending into its mission. A dedicated lending and investment committee evaluates every decision with environmental and social factors in mind.

They offer specialized loans under their Extended Community Climate Change Project. Branch managers and teams receive continuous training in client protection, delinquency management, and fair lending.

They also target ethnic minorities–like the Horijan, Rabidas, and Chowhan–ensuring access to credit, education, and empowerment.

Their internal audit team of 28 members monitors discipline, compliance, and transparency. A central monitoring unit tracks productivity, mitigates risks, and prevents malpractice.

They collect exit interviews from staff and receive complaints from clients through structured channels. They also participate in social and financial forums to learn and share best practices.

He says that most clients report improved quality of life, increased ability to save, better financial planning, higher income, and asset creation.

He believes every product must align with organizational values, serve community needs, and support sustainable growth.

He shares that early in his career, he had the chance to work through different phases of microfinance–from charity-based models to development and finally to commercial approaches.

In one village visit, he met women who had rebuilt their lives through small loans. That moment, he says, changed his view of poverty and the role of finance in creating dignity.

He recalls how during the floods between 1998 and 2007, borrowers still repaid loans in crisis, proving that microfinance is more than just money–it is a lifeline.

He also highlights how they paused collections during the pandemic and refunded savings, showing their commitment to clients’ well-being.

Recently, he has been leading efforts to digitize operations–disbursing loans through mobile channels and adopting AI-enabled tools for faster and safer financial services.

He says the organization started with small steps in practical education and awareness, but soon realized that without financial access, no development was sustainable.

This realization drove them to expand their microfinance programs–and later include healthcare, education and child development, and even rehabilitation efforts for beggar families. He says those efforts helped shape national programs like PKSF’s ENRICH.

Each experience, he says, made one thing clear: microfinance in Bangladesh is not just a tool for poverty reduction. It is a platform for human dignity, inclusive opportunity, and sustainable national development.

Mr. Bhuiyan states–microfinance institutions play a significant role in achieving the food self-sufficiency of our country. However, if these microfinance organizations take special initiatives based on region-specific food habits and demands, and provide financial and technical supports, agricultural production will increase manifold. This will lead to a reduction in commodity (food) prices, benefiting the general population as well, Finally he said.